Posted on: 21/07/2023

Reading matters. As one of the opening sentences in the DFE’s Reading Framework states, “To the individual, it matters emotionally, culturally and educationally; because of the economic impacts within society, it matters to everyone”. Following the initial release of the DFE’s Reading Framework in 2021 which focused on Early Years and KS1, this month’s 2023 update has resulted in a document over twice the size, expanding on previous recommendations to focus on KS2 and beyond, exploring best practice in the teaching of comprehension and developing true reading for pleasure. Having explored the updates in detail, we have pulled together the most salient points to summarise the recommendations and explore how our approach ties in with the latest evidence-based research in best practice for the teaching of reading beyond the use of SSPs.

This was perhaps the most stand-out message of the new framework, which threaded throughout the entire document. Quality text selection is key. For us, this is obviously music to our ears. We know the importance and value of high-quality texts which tackle complex themes, represent all facets of our diverse society, introduce rich literary language and allow children to see both themselves and those who are different to them in the books they read. As the framework states, ‘Literature is the most powerful medium through which children have a chance to inhabit the lives of those who are like them… children also need to learn about the lives of those whose experiences and perspectives differ from their own. Choosing stories and non-fiction that explore such differences begins to break down a sense of otherness that often leads to division and prejudice.’ The criticality of quality texts in the development of empathy also sings loudly throughout the framework. Evidence shows that children who read more have increased levels of social and emotional wellbeing and improved levels of empathy: ‘All pupils should encounter characters, situations and viewpoints that mirror their own lives, so they understand that they matter. Books, however, should also give them a window into the lives of others. For some pupils, stories might be the only place where they meet people whose social and cultural backgrounds and values differ from their own’. The framework also provides a set of questions to support teachers and schools in quality text selection; all of these are questions we consider as a team when we go through the careful and rigorous process of selecting the texts we create Writing Roots and Literary Leaves for, ensuring they have a strong narrative, explore powerful themes, contain rich, lyrical and literary language and reflect a diverse range of voices and characters to allow children to connect with who they are and who they want to be.

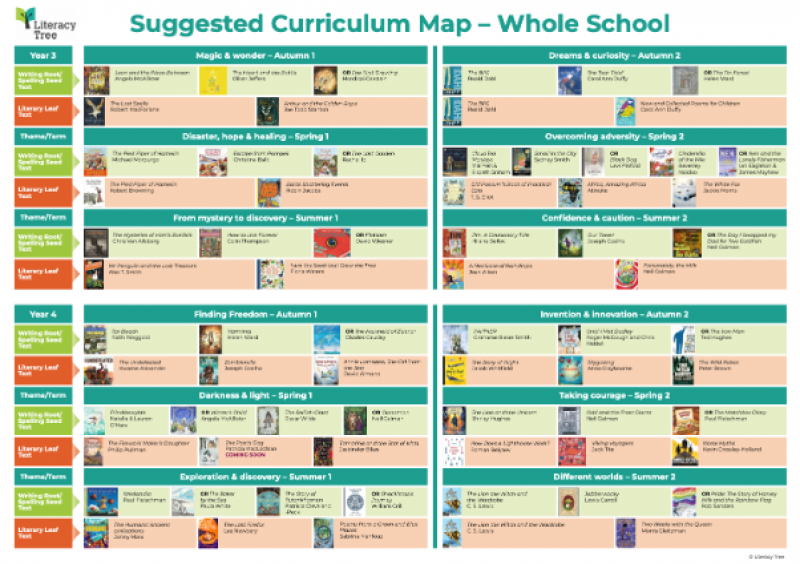

In addition to this, the bigger picture is also important. It’s not just about individual book choices but about how these books weave together to provide children with a rich and varied literary diet across their school journey. A key recommendation of the framework is the identification of a core set of literature for each year group across a school. Are children having the opportunity to experience a wide range of literature in different forms from different time periods and culture? Are they exploring picture books, novels and novellas, poetry and non-fiction to allow them to develop their own preferences and opinions? Are they delving into both contemporary and classic writing by a diverse range of authors? Do they have the opportunity to dive into heritage texts – those classics from the past which still resonate today and allow for rich discussion and making links with modern society? Our curriculum maps do exactly this and this recommendation of careful selection of core texts across the school is absolutely fundamental to our whole raison d’etre at Literacy Tree: developing children’s literary repertoire so that they can comfortably navigate a book shop and foster a life-long love of reading. It’s not just about the book that Year 4 study in Autumn 2, it’s about the whole literary journey a child travels on throughout the course of their time in your school, allowing them to make links between texts and authors and develop their literary bank. Refreshing these maps regularly is another recommendation we feel passionately about. This is why every year in the summer term a large part of our consultancy is spent working with subject leaders and teachers on curriculum mapping for the following academic year; exploring new texts on offer, looking back at what worked well and adapting the maps accordingly.

The importance of teachers reading aloud to pupils across all year groups is paramount in the framework: ‘Reading aloud fosters positive attitudes, enhances pupil motivation to read and develops vocabulary and other knowledge, including of books, authors and genres that they might not choose to read for themselves’. In fact, it even goes as far as to recommend that all primary age pupils should be read aloud to, from a quality text, for a minimum of four twenty-minute sessions per week. As teachers, we know how challenging timetables can be, and so the reality of fitting in an additional 20 minutes story time four times a week or more is not quite as straightforward as they suggest. However, the value of the read aloud can be reflected within the teaching of reading and writing through the use of quality texts. Both our Literary Leaves and our Writing Roots involve lots of opportunities to read aloud to pupils. Not only is this about listening and getting lost in a story to motivate pupils, but also about the modelling of fluent reading. It’s about placing value on the words on the page, and promoting that love of reading through your own enthusiasm and joy in the book. As the framework explains, ‘teachers are the best people to promote a love of reading because children care what their teachers think about the stories they read aloud. If teachers show they love the story, the children are likely to respond in the same way’. The more frequently we as teachers read across the curriculum, the more children experience the impact of fluent reading – they hear what it sounds like, they experience how it makes them feel and the explore the impact on them as a reader. In time, this allows them to understand how pace, intonation and volume can be controlled to add meaning, which words to emphasise and the musicality of text on a page. Reading fluency is not just about accuracy and words per minute.

Whole-class reading teaching based on rich and challenging texts read aloud by teachers is also cited as valuable for those pupils who are less confident readers. This is core to our principles – involving everyone in the journey through a text and scaffolding appropriately to meet everyone’s needs. Reading aloud allows all pupils to access the texts others can read independently so they are still able to encounter the same quality language and ideas, with the teacher able to stop and explain vocabulary or give additional information to support understanding. What’s more, the Framework underlines the importance of ‘all pupils accessing demanding texts’. This inclusivity and the importance of all children enjoying the same book is key to our approach. Specifically, our Literary Leaves are designed with a whole-class reading approach in mind so that all children are equipped to access quality texts. The focus on teacher reading aloud is vital to the success of this, but children with less well-developed language skills may also need further support with this through pre-teaching vocabulary or required background knowledge, pre-reading with an adult, targeted questioning within a session, focus group support during a session or through scaffolded task design to consolidate their understanding.

The importance of reading whole texts rather than extracts is another element of the Reading Framework which we agree wholeheartedly with. The Framework explicitly states that extracts should not be used as a means of covering a range of writing, rather that leaders and teachers must ensure that children enjoy whole texts through a text-based English curriculum (hooray!) or listening to full novels read aloud. While the recommendations seem to conflict entirely with the way in which reading is assessed at the end of Key Stage 2, through exactly the extracts they state we should not be using to teach, this conflict is in fact acknowledged; ‘Giving pupils a short text or extract and asking them to answer questions about it is assessing reading, not teaching it; it may not even be assessing reading very well’. It will be interesting to see whether this has any bearing on any future plans to alter the way in which reading is assessed (here’s hoping!). Experiencing the entirety of a book allows children to explore the richness and depth of the text, get under the skin of the characters and plot, feel immersed in its world and settings and discuss the shift in themes throughout and is essential for fostering reading for pleasure.

The concept of ‘reading for pleasure’ has been a buzz phrase in the world of education for some time, but the Reading Framework now unpicks this further to explore what we really mean by this, and how to develop a true culture of reading for pleasure that goes beyond dress-up days, reading tea parties and points-based systems. A true culture of reading for pleasure permeates throughout a school and hits you the minute you walk in. It jumps out at you when you walk in a classroom and children are falling over themselves to tell you about the latest book they’ve been exploring, whether it’s their outrage at an injustice that’s taken place, their hilarity at an comic incident, or their sadness at a tragic event. It’s something we see when we are lucky enough to go into many of our schools across the country, particularly in our Flagship Schools. Reading for pleasure is not a quick fix: it is a long-term investment that takes years of hard work to develop. The Framework underlines that the strongest predicator of reading performance is engagement of reading, regardless of socio-economic background: ‘making sure children become engaged with reading from the very beginning is one of the most important ways to make a difference to life chances’. Building a true reading for pleasure culture therefore requires a carefully thought-out, strategic approach rather than seeing it as a series of ‘activities’: ‘competitions, dress-up days and promotional activities are not enough’. We need to inspire and engage pupils in reading and that depends hugely on embedding a school culture that places value on reading. Core strategies discussed include regular read-alouds from teachers, book talk, allocating time for reading, sociable reading environments, protected class reading time and rich and varied text selection. Children need to experience the wonder, joy and fascination that comes from losing yourself in a book and putting this at the heart of your English curriculum is one way of achieving this. Celebrating this love of reading and books through displays and published pieces is a great way of sharing and embedding this culture, and we are always blown away by the quality of displays we see in our schools and the pride children show in them.

‘Reading lessons need to create readers, not just pupils who can read’. We love this statement, and the framework goes on to provide detailed explanations of what exactly makes a ‘skilled reader’, including:

Creating mental models as they read, amending and updating what they know with new information

Drawing on their experiences and knowledge to make inferences, filling in gaps as they go

Considering the meaning, implications and nuances of words and phrases, drawing upon wide and deep language banks and bodies of knowledge

Drawing upon their knowledge of sentence structure, including punctuation

Constantly anticipating what might come next and activating meaning.

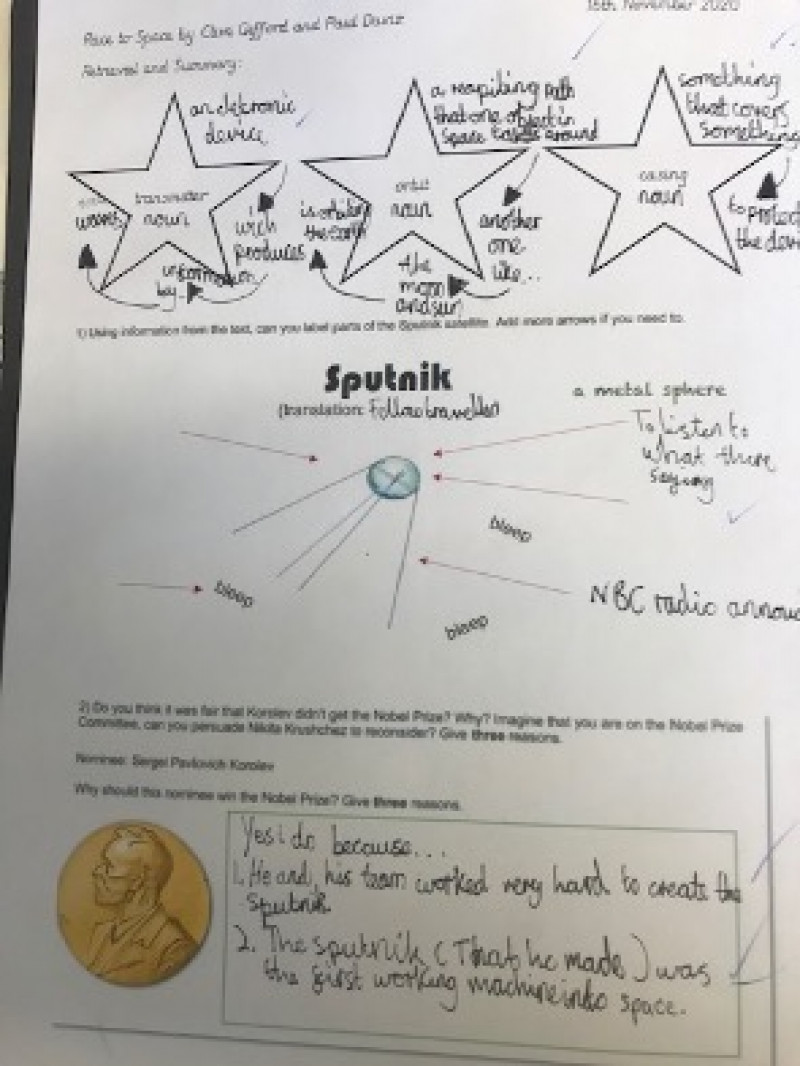

Once pupils can decode, their language comprehension continues to be developed by the amount they read (referred to in the Framework as their ‘reading miles’) as well as the books and other texts they continue to hear read to them, and opportunities to listen and speak. The key driver for improving comprehension therefore is to read a lot, and to listen to and talk about literature read to them. Reading comprehension relies on knowledge and processes working together, and therefore cannot be divided up into individual skills to be taught separately. As the framework states, ‘comprehension is an outcome not a skill to practise’ and it therefore recommends reading lessons covering a range of relevant objectives and strategies, to replicate what skilled readers do and use all the time, rather than just one skill in isolation. This is exactly what our Literary Leaves do – supporting teachers to journey through a text with their children through effective questioning and discussion that draws on strategies across the entirety of the assessment domains as appropriate and relevant to the particular part of the text being explored on a given day. Effective comprehension teaching is not about individual skills teaching in isolation, but about introducing a wide range of literature, increasing and activating children’s knowledge, including explanations, modelling and support from the teacher for different aspects of reading, including fluency. ‘The knowledge, experience and insight that pupils gain from reading a text alongside a teacher then support them to understand and enjoy the texts they choose to read independently’. Effective questioning is specifically mentioned as being key to deepening pupils’ understanding and playing a central role in the effective teaching of reading: ‘questions need to be text specific’. Again, our Literary Leaves do exactly this, so we were thrilled to see the value of these text-specific questions and the importance of a multi-faceted approach to the teaching of reading strategies being highlighted in the Framework.

The importance of talk in the teaching of reading across all key stages was another aspect of the updated Framework we were pleased to see. Talk is critical in the development of language and vocabulary and discussion provides a way of thinking deeply about new knowledge, ideas and concepts. Teachers’ roles in this are underlined in the document too, with the importance of scaffolding ideas, modelling and developing children’s responses discussed too. Book talk and rich discussion about texts is central to our approach and models, quality questions and scaffolds are provided across all our Literary Leaves and Writing Roots to support this.

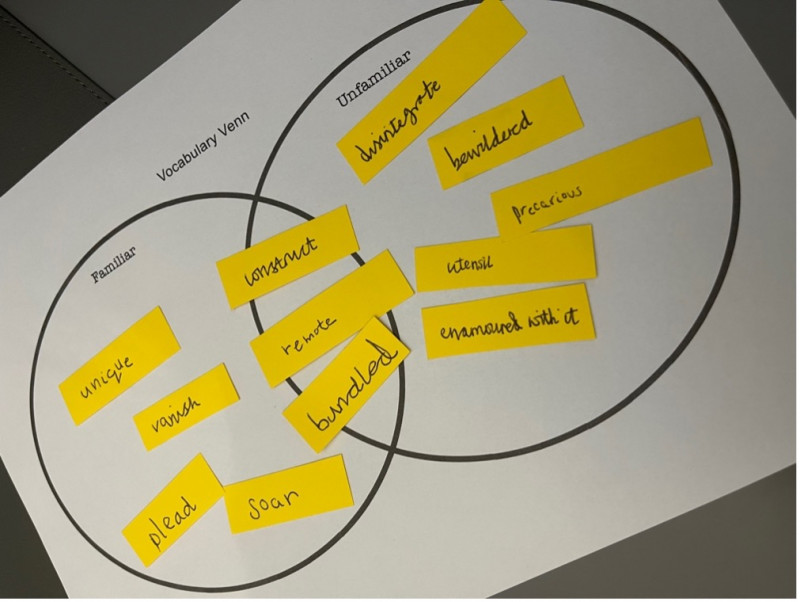

Vocabulary is another area threaded throughout the Framework as a key component in the effective teaching of reading: ‘Listening to, thinking deeply about, and discussing a wide range of texts, including literature, develops pupils’ love of reading and enhances their vocabulary’. This is one of the core principles to our Teach Through a Text approach – we want children to develop ‘word consciousness’ – we want them to be curious about words and language and to foster a culture of intrigue around vocabulary. We know that the best source of rich, new vocabulary which reaches across multiple domains is literature. Through books, children will encounter language they are unlikely to otherwise meet. Often referred to as Tier 2 vocabulary (courtesy of research by Beck + McKeown), this literary language is the focus of much of our vocabulary teaching through our Writing Roots and Literary Leaves. This is the vocabulary and language with multiple meanings and nuances which is applicable across numerous contexts. It’s flexible and adaptable and it is the quality language we want our children to be able to understand, use and apply. The Reading Framework recommends a robust approach to the teaching of vocabulary involving the direct explanation of the meaning of words along with ‘thought-provoking, playful and interactive follow-up’. For us, explicit vocabulary teaching is a core part of all our sequences. This ranges from specific vocabulary to teach prior to reading, to vocabulary development tasks such as Vocabulary Venns, Traffic Light Vocabulary, Language Continuums and Shades of Meaning (see our Classroom Toolkit for more of these!). We also place a strong focus on word families through tasks based around etymology and morphology, particularly within our Spelling Seeds to deepen children’s understanding of the development of language and giving more depth and context to their learning. A particular favourite line of ours is, ‘Tell pupils what words mean – if they already know it, there’s no point in asking, if they don’t, the question is pointless.’ We use the phrase ‘give it for free’ a great deal in our consultancy and training. Make time for teaching them new vocabulary and exploring the language they don’t yet know, rather than asking solely for the children’s suggestions. This provides quality input for all children and allows everyone to participate in the development of their language banks.

So, to round up the key messages we’ve extracted:

Believe it or not, this is a very condensed version of the updated Reading Framework, and we’d recommend subject leaders to read the document in its entirety (all 169 pages of it!) to get the full picture. We hope that this summary has given you a good insight into the key messages and how these tie in with our Teach Through a Text approach.

Posted in: Curriculum