Posted on: 23/04/2024

Children’s use of language comes to life when it has a clear audience and purpose – not just because it is an English lesson or because they must tick their way through a checklist, but rather because they are acutely aware of why they are communicating and who they are communicating to. This growing awareness – when speaking and writing – will dictate the grammatical features and vocabulary they choose to employ and their audience’s reaction will often dictate their success.

Children may even forget it is an English lesson and rather see themselves in a role at that moment, depending on the book being read. This could be as a journalist putting together a story for tomorrow’s publication, concisely shaping paragraphs to accurately inform; a politician weaving together hyperbole to persuade or a mystery author intent on chopping up sentences to jar and entertain. Schools which have instilled a vibrant culture of writing for clear audiences and purposes whenever possible often create the most memorable outcomes for children and adults.

One of our Writing Roots’ central aims is to support schools in creating this culture and, through literature, frame a clear sense of context whenever children put pencil to paper. We don’t want this to be happening in some year groups – often this can be most vivid in EYFS – and not others; we want this to be a culture that permeates the school and underpins each teacher’s English pedagogy.

So…how do we go about creating this culture when teaching children how to communicate effectively? As we get set for the final summer term of 2024, we wanted to put together a few pointers that may help answer this question.

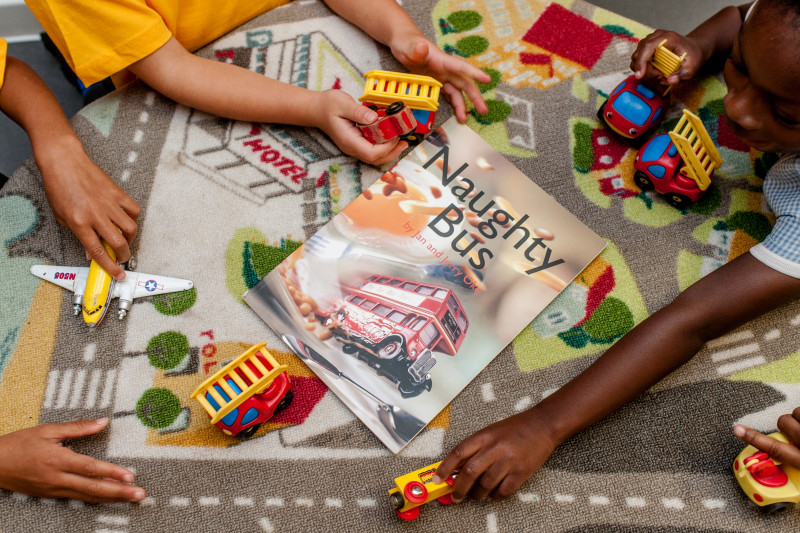

This may seem obvious as most subject specific learning starts in early years, but perhaps a better statement might be, ‘it mustn’t end in early years.’ Early years classrooms are often geared to create this audience and purpose culture with role play opportunities galore; home corners that can morph into restaurants or shops or rockets. These provide rich arenas for speaking, listening and writing.

Children write recipes in the outdoor mud kitchen or take notes on clipboards as they look out a spaceship window, depending on the book the class is immersed in. As we have said in a previous blog, even a child who is at the mark making stage of writing development, can still explain who they are writing to and why they are writing. The key here is to provide opportunities to record in different ways – standing up, lying down, on walls, rolls of wallpaper, till receipts and clipboards to name a few…but how do we keep this sense of wonder in other year groups?

To read more about Literacy Tree in Early Years, check out our blog here.

The start of each Writing Root is bursting with ideas for role play and discussion. These discovery points immerse children in the world of the book and give them time to rehearse new vocabulary and discuss themes vital for later writing in the sequence.

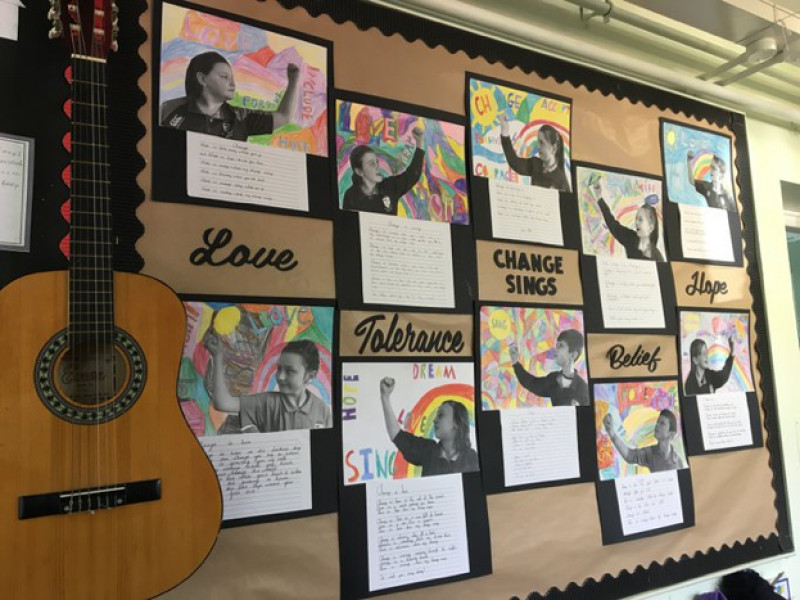

At the start of a new term, if all classes are opening a new text, create opportunities for children to share these discovery points in assemblies and, if possible, videos and pictures can be shared on social media too. This is a great way to create a shared sense of awe and wonder with children and parents alike. Now that the context and themes have been established and the vocabulary explored, the purposeful writing will follow.

To read more about Literacy Tree discovery points, check out our blog here.

To explore the range of whole school Writing Roots Literacy Tree have to offer, check out our resources here.

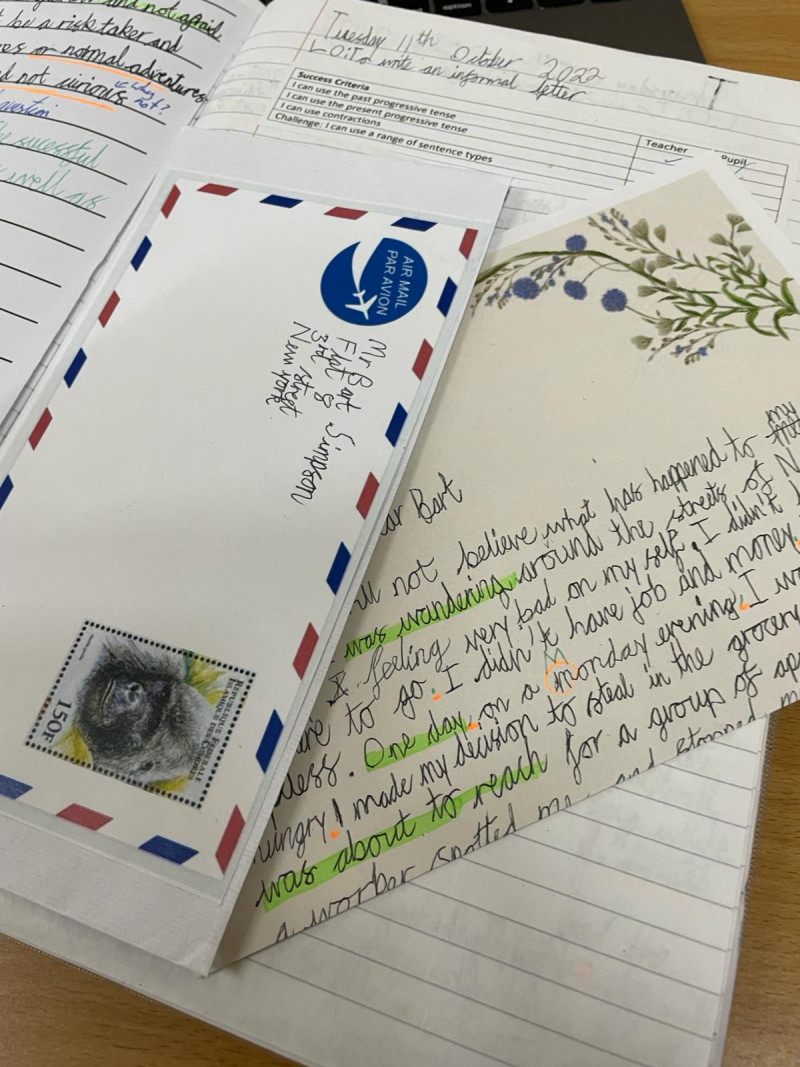

If you have already used Literacy Tree writing roots, you will have noticed the terms planned and instant publishing. Instant publishing refers to the incidental writing opportunities that a class will encounter as they journey through a text whether these be short or long writes. These are opportunities for children to write on ‘special media’. If they are writing as an MP, use special Westminster-headed letter paper. If they are writing a postcard from London, use an actual postcard and place this in a pocket to display in their books. This is not about getting things perfect and doing a first and second draft; it is rather about enhancing this sense of audience and purpose.

Planned publishing refers to the extended write at the end of the sequence. The piece of writing that all the skills and vocabulary explored earlier on in the sequence, build up to. This is when children will edit and redraft with a clear audience in mind and often involves book or pamphlet making.

English books that make the most out of instant and planned publishing opportunities are often brimming with life and colour. Because children are aware that their work will be displayed and published, they are motivated to edit and redraft.

We have discussed the importance of using drama in English lessons. Building on this, it is always effective (and fun!) to transform the classroom into another space entirely. As children enter the classroom, the teacher can explain that this is no longer a classroom, instead this is now an archelogy department, and we are archaeologists about to embark on a dig. This is now Rosie Revere’s School of Engineering or we are now trainee engineers about to solve a problem. Where possible, it can be powerful to make these imaginary spaces aspirational in nature, opening children’s minds to the various careers and possible future pathways they may decide to take.

Whatever pathway they decide on, we hope they will have had a range of experiences at primary school, seeing and using language as an effective tool to entertain, inform and persuade.

Posted in: Curriculum