Written byAlex Francis

Senior Consultant & Resource Manager

See More

At Literacy Tree, we are huge advocates of the value of wordless texts. Communicating through pictures on cave walls was the very first form of storytelling some 40,000 years ago, so this ancestral literary legacy living on must mean something. However, despite their popularity, wordless books often remain overlooked in the teaching of reading, commonly and mistakenly confined to the realm of reluctant or struggling readers.

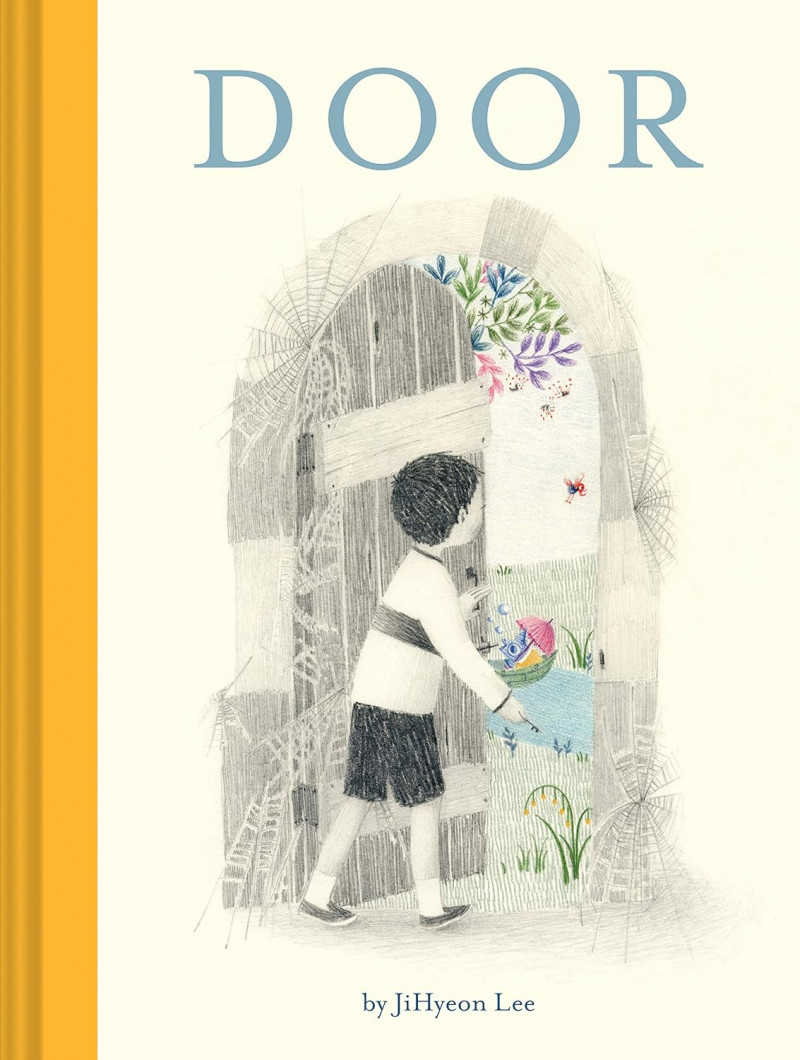

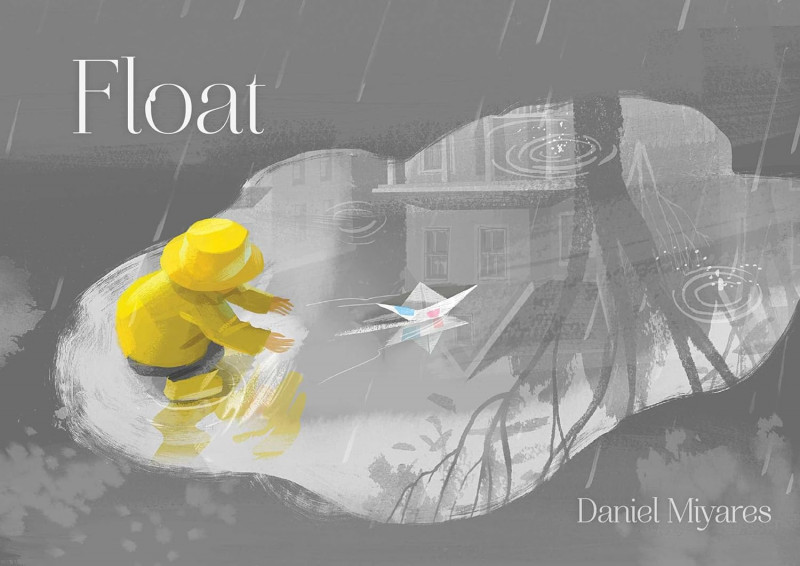

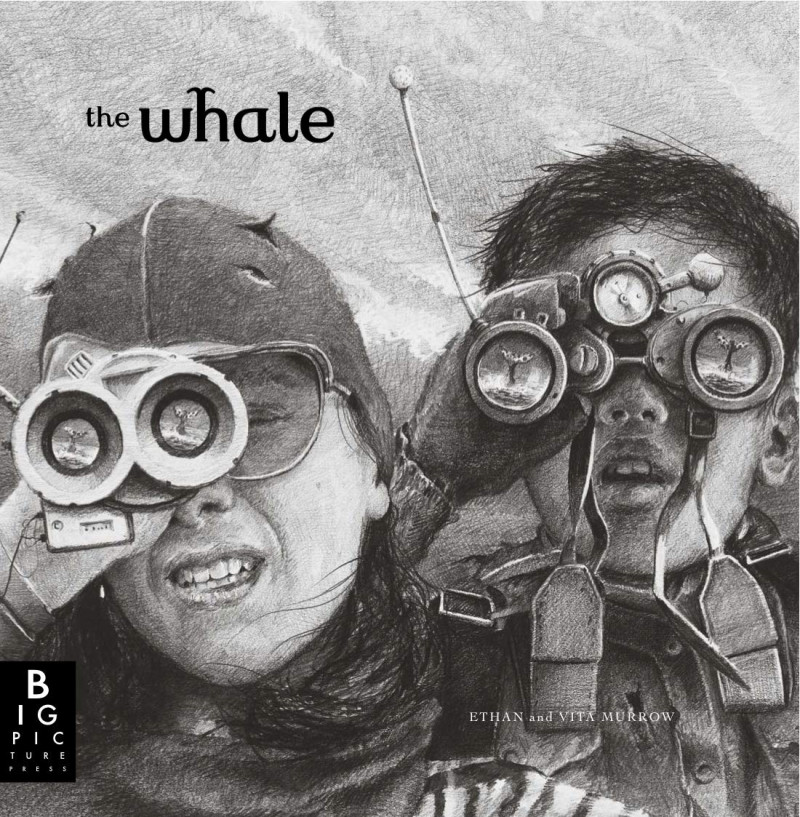

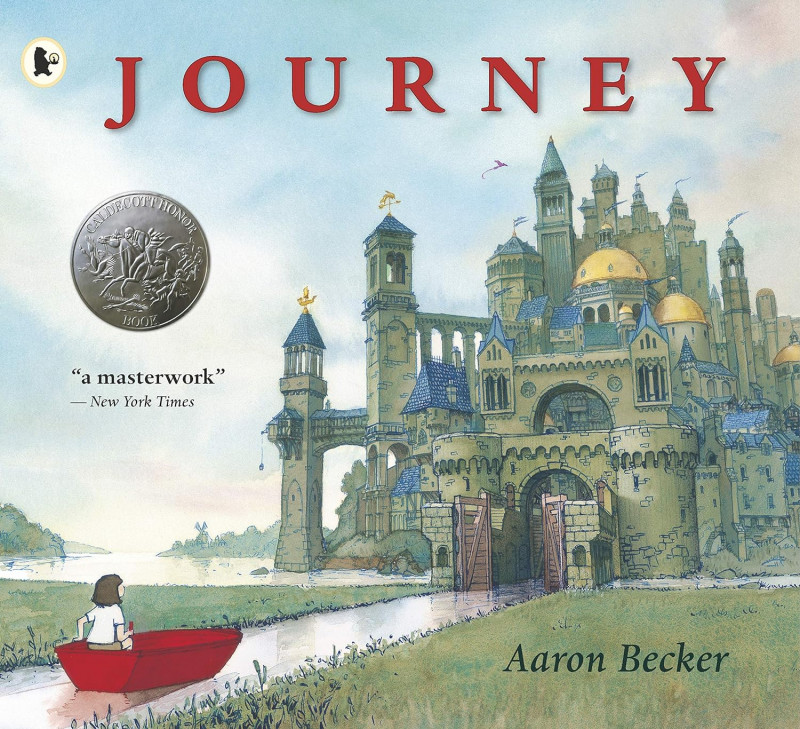

With the increased emphasis on, yet lack of definition of ‘literary merit’ in the most recent Ofsted English Subject Report, and the huge focus on fluency, wordless picture books are at further risk of being discounted from schools’ literary canons. ‘Literary merit’ is hugely subjective and Ofsted’s unwillingness to define it proves problematic. While complex and rich vocabulary may play a part, this cannot be its sole criteria. Reflections of readers’ own experiences, doorways into the lives of others, exploration of diverse settings and characters, grappling with challenging themes and raising issues of social justice must also be strong contributors to this merit – and wordless texts can offer this in abundance. Like paper gateways into worlds limited only by readers’ imaginations, wordless texts let the pictures do the talking - and my, do they do some talking. Books that tell stories through nothing more than illustrations can stimulate intense debate, encourage deep discussion, broaden minds, develop visual literacy and inspire imagination just as much, if not at times even more so, than their worded counterparts. So what exactly is it that makes wordless texts some of the most captivating books to read with children?

Creativity, imagination and depth of thinking

Wordless texts require us to slow the pace. We need to look, look and look again to unpick the visual narrative - each reading offering something different to the last. By lingering and pouring over a wordless story we lengthen our processing time – both wandering and wondering our way through the images and unpicking all the possible avenues they offer. The stories are hidden within the illustrations – and while every brush stroke, line or mark is placed with intent by the artist to tell a specific tale, the interpretation remains in the hands of the reader. Wordless picture books allow us to soak up and digest the narrative according to our own lived experiences and views of the world, resulting in limitless unique constructs of the story. When words are removed, we can actively participate in and engage with constructing the narrative, and when exploring with others, compare and contrast our interpretation with theirs. Children are not restricted by the words on the page but instead can narrate the story through their own eyes, gaining confidence and ownership of the story they are telling.

Inclusivity and accessibility

Despite wordless texts often mistakenly being categorised as only for struggling or reluctant readers, it cannot be denied that they are highly accessible and inclusive. They break down language barriers and provide low threshold, high ceiling opportunities for all children to access and engage with rich, quality narratives. For children new to English, for example, they are a brilliant tool for engaging in high level inference. While some wordless texts are undoubtedly more appropriate for certain ages, as a general rule they level the playing field for readers, allowing everyone to construct their narratives and engage in deep inference and complex themes which might be difficult for those children to access if relying on words alone or decoding ability.

Interaction and language development

Research has shown that levels of interaction between caregivers and children are notably different when exploring a wordless picture book compared with a worded text. On a simple level, in a book sharing context, wordless texts require greater levels of adult participation and engagement than their worded counterparts. More questioning, collaboration, discussion and improvisation are required when navigating these books with children when there is no text on which to structure the interaction. Research studies have equated wordless texts with open-ended play-based activities (think Play Doh and Lego) where carers and children converse while playing, rather than following a rigid format. Researchers found, in essence, that in home reading scenarios, wordless texts generated more language from a child than books with words due to their open-ended nature. Seeing wordless texts as an opportunity for parents and caregivers to ‘play’ with their children through an original interpretation and interaction is an interesting consideration for schools to take when thinking about ways of improving oracy.

Understanding of text structure

Wordless texts can prove useful tools in supporting children’s understanding of how to structure a cohesive and coherent narrative. Without words, the connections and links between every picture are vital. With no text markers to indicate movements in time, location or character, the role illustrations play in signalling such movements clearly is critical. Wordless texts can be structured in a variety of ways – some artists prefer single images on each page or double page, while others prefer more of a graphic novel approach with multiple images organised on the page, which can sometimes be trickier for readers to navigate. Readers need to be able to read the illustrations both individually and as a collection and as such, wordless books can support them to stitch the stages of the narrative together to make meaning.

Application of reading skills

Wordless texts offer a plethora of opportunities for the teaching of specific reading skills, offering countless ways to support the process of meaning making and constructing mental models of texts. Reading pictures lends itself perfectly to the skill of inference, allowing readers to dive deeper into the hidden meaning behind the illustrations and the characters within them. Without the added clues of text, readers need to look in-depth at what is in front of them, to really get under the skin of the artist’s intent. The concept of ‘show, not tell’ is taken to a different level with wordless texts, with more focus on facial expressions, body language and the use of colour, composition, shade and sizing to convey emotion. All of these elements can contribute to deep levels of empathy and inference. When you consider comprehension as an outcome, not a skill, you can see how wordless books offer countless opportunities for readers to combine, practise and apply the strategies of predicting, summarising, retrieving, comparing and analysing. Pictures are the language of the book; they need to be read just as carefully as the text in a worded book.

While the English subject report may fail to define literary merit, it does however recognise that ‘comprehension comes from accessing a wide range of texts and encountering different forms and concepts and includes having a wide knowledge of the world.’ Quality wordless texts offer limitless possibilities for rich discussion, deep thinking and the opportunity to see the world through different lenses, and in that sense, we will always hold them in the highest literary merit. As Jessica Winters so astutely writes, ‘by excluding what readers might otherwise assume to be a main ingredient, the wordless picture book heightens the flavours of what remains’. And wow, are those flavours good.

You can explore some of our favourites here.

Posted in: Book Choice | Curriculum | Diversity